New Forest bat surveys - 2025 results

- Russell Wynn

- 2 hours ago

- 8 min read

Prof Russell Wynn (Wild New Forest)

Introduction

The New Forest National Park is recognised as a national hotspot for bats, with at least 14 of the 18 UK species recorded to date. However, due to their nocturnal habits, bats remain under-recorded compared to more accessible species groups, and there are many gaps in survey coverage. Acoustic detection is an important tool in the bat surveyor’s toolbox, with modern weatherproof detectors able to be deployed remotely on site for long periods in all seasons. Although acoustic detection is inevitably biased towards the more vocal and easily identifiable bat species, it is nevertheless a useful method for identifying hotspots for foraging bats and locations where priority species are occurring.

In 2025, the author deployed acoustic detectors at 20 sites in the New Forest National Park as part of broader baseline ecological surveys (Fig. 1). At all survey sites, landowners are being supported by various partners to deliver conservation management, including creation and restoration of wetland, woodland, grassland, and heathland habitats. The 2025 bat survey data presented here therefore provide a potentially useful baseline against which future (hopefully positive) changes in bat activity can be measured.

Figure 1: Map of the New Forest showing approximate locations of the survey sites in this study. White circles = SSF sites; yellow circles = private estates/holdings with multiple sites. Dark green is Forestry England land, mid green is New Forest National Park, orange and yellow shading is local and national nature reserves, and hatched areas are SSSI. Map data from OpenStreetMap.

Five static acoustic bat detectors (Wildlife Acoustics Song Meter Mini Bat 2) were available for the survey, with a single detector deployed at each site for an average duration of about 20 nights. A total of 1.2TB of acoustic data was generated during the year, primarily bat calls (known as bat passes) but also including stridulating bush crickets and nocturnal/crepuscular bird sounds. The acoustic data were automatically classified to species level using the BTO Acoustic Pipeline, with manual cross-checking of notable bat species undertaken using Kaleidoscope Lite software. Further details of the survey methods and limitations are appended, and all survey data will be provided to Hampshire Bat Group and Wiltshire Bat Group.

Summary results

At least 11 bat species were recorded during the survey. Of these, eight species were confirmed with high confidence (Table 1), with just under 375,000 individual bat passes across 20 sites over a total of 600 deployment nights.

Table 1: Summary bat data from all 20 sites surveyed in 2025, showing number and percentage of sites where each species was recorded, and the number and percentage of total high/medium confidence bat passes for each species.

Soprano Pipistrelle was the most frequently detected species at 191,420 passes, followed by Common Pipistrelle at 161,492 passes; both species were recorded at all 20 survey sites and together accounted for just over 94% of all bat passes (Table 1). Natterer’s Bat, Noctule, and Brown Long-eared Bat were also widespread, and together account for another 4.5% of the total. Two red-listed ‘Vulnerable’ bat species were regularly detected: Barbastelle at 20 sites with 2000 passes, and Serotine at 17 sites with 2128 passes (Table 1); both species were widely distributed across the survey area and are known to travel long distances to forage. Greater Horseshoe Bat is a rare species in the New Forest, so it was notable that the species was recorded at two sites.

A further three bat species were sporadically recorded, but with reduced confidence due to challenges with acoustic identification: Nathusius’ Pipistrelle and Leisler’s Bat were both recorded at one site each (and are classified as ‘Near Threatened’ on the most recent red list), while Daubenton’s Bat was also confirmed at one site where the diagnostic social calls were detected.

Bechstein’s Bat, Brandt’s Bat, and Whiskered Bat were detected in small numbers based on automatic classifier outputs, but these Myotis species are acoustically quiet and challenging to identify to species using acoustic data alone and so remain unconfirmed.

The following sections provide further details of survey results from 11 sites that were surveyed as part of the New Forest Species Survival Fund project, and from a further nine sites across three private estates/holdings that were surveyed as part of commissioned ecological baseline surveys.

Species Survival Fund (SSF) sites

A total of eight bat species was recorded with high confidence at the 11 SSF sites (Fig. 1), with just over 140,000 individual bat passes over a total of 178 deployment nights.

Table 2: Summary bat data from the 11 SSF sites surveyed in 2025, showing total number of high/medium confidence passes at each site for each species. BLEB = Brown Long-eared Bat; GHB = Greater Horseshoe Bat.

Common and Soprano Pipistrelle were the two most frequently detected species, accounting for nearly 94% of all detections (Table 2). Barbastelle was recorded at all sites, with 418 passes recorded at one parkland site, while Serotine was recorded at all but one site. Greater Horseshoe Bat was recorded at two sites, with two passes at one site and 35 passes at another site (Fig. 2). At the latter site, analysis of the timing of bat passes indicated that the site was probably close to a daytime roost. Both sites were in Wiltshire in the vicinity of Langley Wood National Nature Reserve, an area where the species is known to occur and where Wiltshire Bat Group are working to survey and support the species.

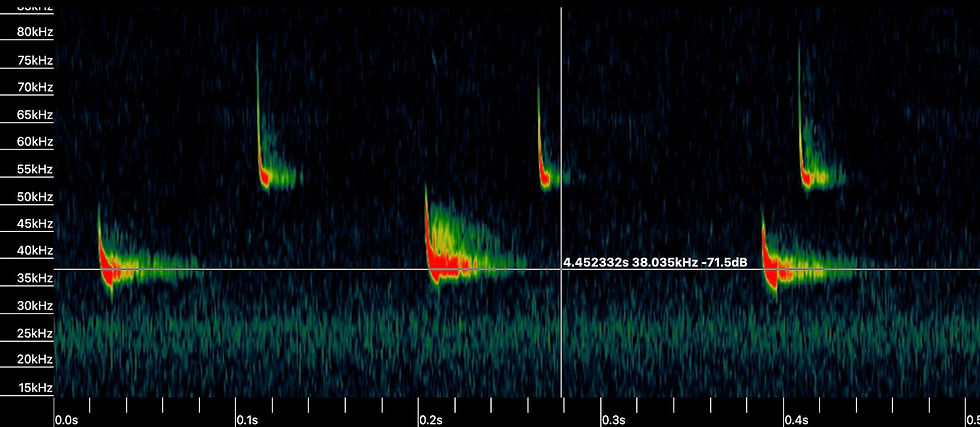

Figure 2: Spectrogram generated in Kaleidoscope Lite showing Greater Horseshoe Bat echolocation calls on 17 May 2025 at a New Forest SSF project site; note the distinctive call shape and peak frequency at 82kHZ, with the weaker first harmonic peaking at 41kHz.

Other notable records included a total of 603 Nathusius’ Pipistrelle passes at one site, including several that were confirmed via manual analysis (Fig. 3), although some also appeared to be misclassified Common Pipistrelles. Leisler’s Bat was potentially detected at one site, although this is a tentative result and only 12 passes were recorded (Fig. 4).

Figure 3: Spectrogram generated in Kaleidoscope Lite showing Nathusius’ Pipistrelle echolocation calls on 17 May 2025 at a New Forest SSF project site; note the peak frequency at 38kHZ, with calls of Soprano Pipistrelle showing peaks at 55kHz.

Figure 4: Spectrogram generated in Kaleidoscope Lite showing possible Leisler’s Bat echolocation calls on 05 May 2025 at a New Forest SSF project site; note the peak frequency at 24kHZ, with calls of Common Pipistrelle also shown with peaks at 45kHz.

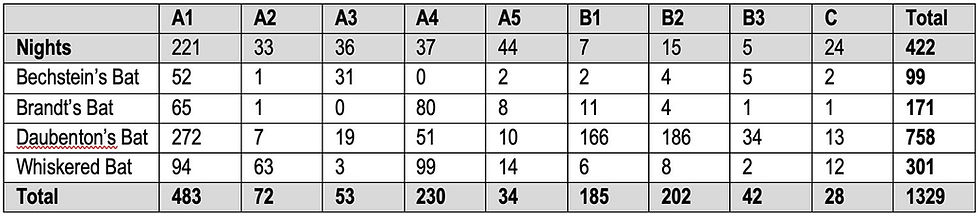

Of the Myotis bats, Daubenton’s Bat was confirmed at one site based on the distinctive social calls (Fig. 5), while echolocation calls attributed to this species were detected at all 11 sites (Table 3). Although acoustic separation of Myotis bat echo-location calls is challenging, the automatic classifier outputs indicate three locations where Bechstein’s Bat was detected at least once per night (on average), and a couple of sites where Brandt’s/Whiskered Bat were also regularly detected (Table 3); these sites may be future targets for trapping studies.

Figure 5: Spectrogram generated in Kaleidoscope Lite showing diagnostic ‘umbrella handle’ social calls of Daubenton’s Bat on 29 May 2025 at a New Forest SSF project site.

Table 3: Summary bat data for four Myotis species from the 11 SSF sites surveyed in 2025, showing total number of high/medium confidence passes at each site for each species.

Other private sites

A total of seven bat species was confirmed at nine additional private sites, which are concentrated on three large private estates/holdings (Fig. 1). A total of just over 140,000 individual bat passes was recorded at these sites over a total of 178 deployment nights (Table 4).

Table 4: Summary bat data from the nine private sites surveyed in 2025, showing total number of high/medium confidence passes at each site for each species.

As with the SSF sites, Common and Soprano Pipistrelle were the two most frequently detected species, accounting for nearly 95% of all detections (Table 4). Barbastelle was also recorded at all sites, with the highest frequency of detections again being in parkland habitat, while relatively high levels of Serotine activity (about 20 passes per night) was recorded at two sites.

Nathusius’ Pipistrelle was recorded briefly on two occasions on one private estate, on 04 Apr 2025 and 05 Nov 2025; these were assumed to be transitory individuals (possibly migrants, given this is a migratory species).

Of the Myotis bats, the automatic classifier outputs indicate that the echolocation calls of Daubenton’s Bat were detected at all nine sites (Table 5). In addition, there were regular detections (averaging one per night) of Bechstein’s Bat at one site, and two locations on the same private estate where Brandt’s/Whiskered Bat was regularly recorded; the latter will be a target for trapping surveys in 2026 conducted by Hampshire Bat Group.

Table 5: Summary bat data for four Myotis species from the nine private sites surveyed in 2025, showing total number of high/medium confidence passes at each site for each species.

At one location (Site A1; see Tables 4 and 5) an acoustic detector has been deployed since 03 May 2025, recording data near-continuously for 221 nights up to 31 Dec 2025. The aim is to assess seasonal changes in bat activity, with a particular focus on the hibernation period from November to March where bats spend most of their time in torpor. Data collected in Nov-Dec 2025 provide evidence for simultaneous emergence of multiple bat species on nights with mild, calm, and dry conditions, e.g. 5700 passes of six bat species were recorded overnight on 15/16 Nov 2025. The results of this long-term deployment will be analysed in detail in spring 2026, after a full year of data has been collected.

Survey methods and limitations

This survey used Song Meter Mini Bat 2 detectors and mostly targeted woodland edges and rides overlooking grassland and wetland habitats where future conservation action is being targeted. The detectors were secured to suitable trees using a Python cable lock and were located away from vegetation and other clutter at a height of 1.5-2.0m (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Acoustic bat detector fixed to a Scots Pine overlooking an open wetland and heathland site on 15 May 2025, surveyed as part of the New Forest SSF project.

Most deployments covered at least 10-15 days, but at sites with particularly high levels of Common/Soprano Pipistrelle activity and/or stridulating bush-crickets (primarily in the late summer and early autumn period) the 64GB memory cards occasionally filled up within a few days.

Once the memory cards were recovered, the raw WAV files were uploaded to the BTO Acoustic Pipeline for automatic classification (note that the settings for each detector followed the pipeline guidelines, see here). Pipeline outputs can be sorted in a spreadsheet, allowing non-bat data and any low-confidence bat passes (i.e. confidence levels <0.5) to be discarded. Analysis was then conducted on the remaining high/medium confidence bat passes (high confidence passes are those with confidence levels of >0.9 and medium confidence >0.5).

A random selection of recordings of some species (e.g. Barbastelle, Natterer’s Bat, and Serotine) was manually checked using Kaleidoscope Lite software, together with most recordings of scarcer species such as Greater Horseshoe Bat, Leisler’s Bat, and Nathusius’ Pipistrelle.

The echo-location calls of the following species remained unconfirmed due to challenges with acoustic classification: Bechstein’s Bat, Brandt’s Bat, Grey Long-eared Bat, and Whiskered Bat. In addition, all Lesser Horseshoe Bat and most of the classified Greater Horseshoe Bat passes were discarded, as manual checking indicated they were incorrectly classified. The classifier also seemed to particularly struggle with Nathusius’ Pipistrelle, possibly because many of the survey sites were in relatively open locations where Common Pipistrelles often call at frequencies close to 40kHz. Therefore, only Nathusius’ Pipistrelle passes that were consistently at or below ~38kHz (Fig. 3) were treated as confirmed for this study.

Acknowledgements

Nik Knight, Colleen Hope, and Paul Hope of Hampshire Bat Group, Gareth Harris of Wiltshire Bat Group, and Chris Dieck of RSPB are thanked for their helpful feedback and support through the year. Thanks also to all project partners and landowners for facilitating site access. The Species Survival Fund was developed by Defra and is being delivered by the National Lottery Heritage Fund in partnership with Natural England and the Environment Agency. Wild New Forest is a delivery partner of the New Forest SSF project, alongside New Forest National Park Authority as lead partner, and Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, Freshwater Habitats Trust, Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust, and the New Forest Commoners Defence Association. The New Forest Biodiversity Forum is providing SSF match funding to support three years of post-project ecological monitoring at selected sites.